Mira was searching for a new laptop. She found two ads for the same model at two different stores.

Ad A: “Get ₹10,000 off on this premium laptop!”

Ad B: “Limited-time offer: Buy now for just ₹90,000!”

Even though both deals meant the final price was ₹90,000, Ad A felt more like an exceptional deal. ₹10,000 off? That sounded like a huge saving! Ad B, on the other hand, just stated the price—it didn’t feel like a deal.

Mira rushed to the store running Ad A’s promotion and happily bought the laptop, convinced she was getting a great bargain. Later, she saw the same laptop at another store, where the price tag had always been ₹90,000—no flashy discount banners, no urgency. It was the same price, but because the first ad had framed it as a discount, Mira felt like she had made a smarter choice.

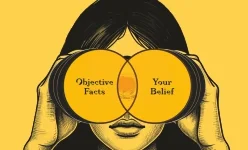

This is Framing Bias—where the way information is presented changes how we feel about it, even if the facts remain the same.

Would you rather buy a “90% lean” burger or a “10% fat” burger? Most people instinctively go for the first, even though both are identical. Hospitals that say “90% survival rate” instead of “10% mortality rate” sound more reassuring, even when the risk is the same.

Marketers and advertisers use framing all the time—whether it’s discounts, food labels, shopping for clothes or product descriptions—to influence choices without changing the facts. And like Mira, we often don’t even realize we’re being swayed.